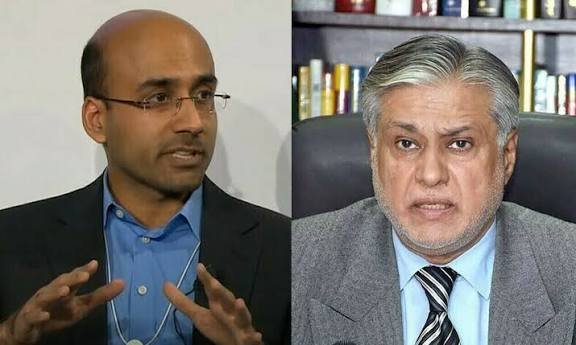

ISLAMABAD – In a nation grappling with chronic economic woes, remittances from overseas Pakistanis have long been hailed as a vital lifeline, injecting $38 billion annually – equivalent to 10% of GDP – into the economy. Yet, a provocative new analysis by economist Atif Mian questions this narrative, arguing that these funds, born from the grueling sacrifices of 10 million expatriates toiling in low-wage jobs abroad, are ensnaring Pakistan in a “macroeconomic trap” rather than propelling it forward.

Mian’s essay, published on his Substack, paints a stark picture of remittances as a double-edged sword. On one hand, they represent “free foreign exchange” from migrants enduring cramped living conditions in Gulf states and beyond, far exceeding the norm for countries at Pakistan’s income level – twice the expected ratio, as shown in comparative economic charts. Families back home rely on these transfers for survival, boosting immediate consumption and stabilizing household finances amid inflation and unemployment.

However, the influx appreciates the rupee, triggering a classic “Dutch disease” effect: exports in tradable sectors like textiles and agriculture suffer as the currency becomes overvalued, making Pakistani goods uncompetitive globally. Investment-to-GDP ratios languish at historic lows, while consumption soars, perpetuating a cycle of stagnation. “If remittances are not managed properly, they can become a restraint on growth,” Mian warns, highlighting how this dynamic sustains elite rent-seeking in non-tradable industries like real estate, where politically connected tycoons convert windfalls into foreign assets.

The irony is bitter: the sweat of poor laborers abroad inadvertently bolsters the purchasing power of the privileged at home. Pakistan’s export slump and prolonged currency overvaluation underscore the malaise, with bad policy – not migrant toil – as the culprit.

Mian offers a roadmap out: The State Bank should aggressively build reserves during inflow spikes to curb overheating. A targeted foreign direct investment (FDI) strategy could channel funds into high-tech, export-oriented greenfield projects, mandating local partnerships for technology spillovers. Discourage speculative portfolio inflows and real estate bubbles to prioritize productivity.

“Remittances don’t have to be a drag on growth. With the right macro policy, they can become a catalyst for financial stability, investment, and long-run development,” Mian concludes. As Pakistan eyes IMF talks and fiscal reforms, this critique arrives at a pivotal moment. Will policymakers heed the call, transforming expatriate resilience into national renewal, or let the trap tighten?